Authors

Josip Pervan, Senior Manager, Policy Advocacy & Member mobilization

Background

The Aichi Biodiversity Targets, established during the 2010 UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), aimed to tackle environmental degradation and included goals such as halving deforestation and reducing pollution’s impact on ecosystems. However, these targets lacked specificity and metrics for tracking progress, hindering its implementation. Although some progress was made toward objectives such as conserving land and ocean territories, none of the 20 Aichi Targets were met globally. Lack of adequate financing, insufficient monitoring and limited government buy-in contributed to their failure.

The lessons learned from this missed opportunity were visibly incorporated into the design of the Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF). Adopted in Montreal in December 2022, the GBF has 23 targets and 4 goals, with a 2030 deadline. It emphasizes a whole-of-society approach, involving governments, businesses and civil society. The GBF includes a more robust monitoring framework with headline indicators, calling for enhanced transparency and accountability mechanisms. It also includes a provision for a periodic global stock take of progress and targets for increasing financial resources from all sources and a commitment to mobilize at least USD $200 billion annually from public and private sources.

The upcoming CBD COP16 meeting in Cali, Colombia, will serve as a first checkpoint for our collective progress toward achieving the GBF objectives.

The cause for optimism

Along with having a better structure in place and measurable top-headline objectives, several significant developments took place over the past decade to create a more conducive environment for the required changes. For instance:

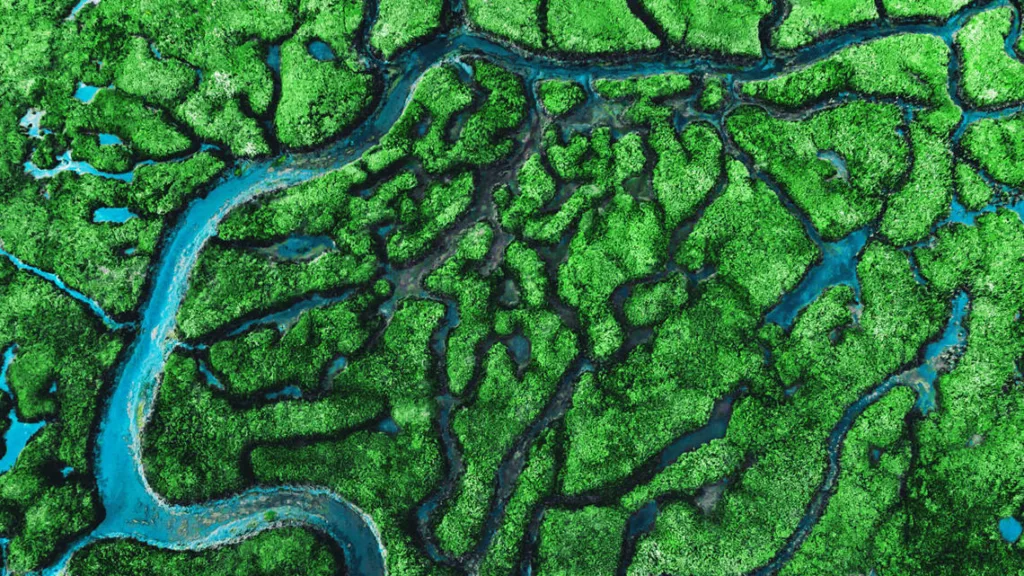

- Evidence from the Dasgupta Review, IPBES, IPCC and the Planetary Boundaries highlights the urgent need for biodiversity conservation. The interdependence of humans and nature and economic risks pressure governments and key stakeholders to act. Healthy ecosystems are crucial for climate regulation and economic stability, driving increased urgency from technology advancement and public awareness.

- Stakeholders such as regulators, investors or consumers are raising expectations for businesses to address nature loss. Companies now recognize this as a material risk, with many setting voluntary targets and adopting strategies that credibly contribute to nature positive for competitive advantage, though challenges in measurement and resistance to change persist.

- Climate change and nature loss are converging global agendas. Nature-based solutions are emerging as key actions to deliver both on the Paris Agreement and the Kunming-Montreal Framework and support the integration of nature and biodiversity into policies.

What are the risks involved?

Translating global targets into actionable national policies and ensuring effective governance and coordination across diverse sectors is not a straightforward task and there is not one single recipe for success. Governments often face multiple pressing issues that may take precedence over nature in national budgets and policies. Without strong political commitment at national and international levels, the ambitious targets of the GBF will not be translated into concrete actions and policies. Additionally, there is a significant funding gap, with concerns about mobilizing and distributing financial resources effectively to support biodiversity initiatives, particularly in developing countries.

In addition, certain parts of the farmer community supported by political movements have voiced concerns about the trade-offs between biodiversity protection, food security and farmer livelihoods, as was evident during the adoption of the EU Nature Restoration law.

While governments play a crucial role in implementing the GBF by setting national policies and regulations, the effective implementation of the GBF requires a “whole-of-society” approach. Integrating key stakeholders, with business at the forefront, ensures that biodiversity targets can be properly mainstreamed across sectors to foster and accelerate action to halt and reverse nature loss by 2030.

The role of the business community

Businesses are an essential element to secure the full implementation of the GBF. Even though the language of Target 15 from the Biodiversity Plan did not mandate businesses to measure and disclose their dependencies and impacts on Nature, the ambitious business community is already actively working on assimilating Nature’s positive work in their business strategies.

Companies can proactively manage nature-related risks by utilizing WBCSD’s Roadmaps to Nature Positive, which has been developed in collaboration with 75 member companies and over 50 partner organizations. By following the guidance in these roadmaps, companies can conduct value chain materiality screenings, identify priority actions to mitigate negative impacts, implement restoration and regeneration approaches, set science-informed targets and prepare for both voluntary (such as SBTN, TNFD) and mandatory (CSRD) disclosures.

How do we make it happen?

1. Create ambitious National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans (NBSAPs)

With CBD COP16 upon us, only a handful of countries and the EU have submitted their NBSAPs. Further submissions can be expected in the period until the conference. Current progress is lagging and needs more speed and scale. To achieve our common GBF objectives, we need robust national action plans with clear timelines, responsible entities and budget allocations for each target. A participatory approach actively involving business and finance communities also ensures meaningful contributions to government strategies.

Ideally, NBSAPs should be produced together with an accompanying finance plan that details the resources and their distribution for implementation. Inspiration can be drawn from the discussions on investable Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). The aim is to transform NDCs into comprehensive investment plans that attract private sector finance and align with climate goals. This approach involves integrating clear sectoral implementation plans and financial needs, thus facilitating access to funding and ensuring effective execution.

2. Build a compelling implementation and monitoring mechanism and reporting systems to hold countries accountable

Discussions on the implementation mechanism during the upcoming COP16 will look at the operationalization of the monitoring framework, which includes the indicators for each of the 23 targets to enable governments to report on progress.

3. Adopt integrated approaches to ensure biodiversity conservation is addressed alongside other global challenges

This requires coordination across sectors and the incorporation of biodiversity considerations into broader policy frameworks. This entails integrating biodiversity into policies, regulations, and practices to ensure that conservation objectives are prioritized and implemented at all levels. WBCSD has co-developed the call to action on the implementation of biodiversity in policies.

4. Increased funding and resources

Negotiations will focus on mobilizing resources to achieve Target 18 (reforming harmful subsidies) and Target 19 (USD $200 billion for conservation by 2030). Innovative financing mechanisms like grants, loans, and the Finance for Biodiversity Pledge signal potential for private sector investment. Governments should create incentives for this, alongside increased support from developed nations to developing countries. Existing funds, such as the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and the Global Biodiversity Framework Fund, should help reduce the red tape and speed up the implementation of transformational projects in most impacted regions.

5. Foster greater engagement and collaboration among governments, businesses, civil society, indigenous peoples and local communities

Meaningful participation and partnerships are essential for implementing effective conservation measures that consider diverse perspectives and priorities. Recognize and respect the rights of indigenous peoples and local communities to manage and conserve biodiversity on their lands. Empowering these groups as stewards of biodiversity contributes to conservation efforts and promotes social equity and cultural diversity.

6. Dispelling misinformation to address populist narratives and how they influence political decision-making

A multi-faceted strategy is needed that includes engaging in dialogue with farmer communities and other affected stakeholders to understand their concerns. Educating on the long-term benefits of biodiversity conservation for food security and wider society while providing incentives for sustainable agricultural practices is required. Collaboration among farmers, environmental organizations and government agencies is crucial for initiatives that balance ecological and agricultural goals. Sectoral policy integration and a long-term vision and commitment by the government to sustainable development are vital for building support for biodiversity efforts. Public awareness campaigns can educate consumers about the link between biodiversity and food security, while success stories of profitable, biodiversity-friendly farms can inspire others. Finally, addressing misinformation through fact-checking and transparency is key to dispelling concerns and providing reassurance.

In summary, we are now much better positioned to succeed in implementing the GBF. Yet, there are still significant challenges to be overcome. The progress of work on NBSAPs and financing, in particular, leaves room for improvement. We hope that COP16 will inject new vigor and propel us to a happier, nature-positive future.

Outline

Related

Content

Accelerating business accountability, ambition and action and in support of Global Biodiversity Framework implementation

9 December, 2022

COP15 reflections: how is business stepping up to implement the Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF)

20 December, 2022

Road to COP 15: aligning business action with the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework and 2030 Action Targets

29 June, 2022